Αγαπητοί αναγνώστες:

Μπορείτε να υποστηρίξετε την προσπάθεια να μετρήσουμε το αθέατο κόστος του κράτους ψηφίζοντας εδώ.

ΕΛΣΤΑΤ - Ελληνική Στατιστική Αρχή: Μετρήστε πόσο από το χρόνο τους αφιερώνουν οι Έλληνες πολίτες στο Κράτος

Γιατί είναι σημαντικό;

Κανένας δεν γνωρίζει πόση από την καθημερινή ζωή των Ελλήνων Πολιτών αναλώνεται στο να εξυπηρετούν το ελληνικό Κράτος - να του παράσχουν πληροφορίες, δικαιολογητικά, δηλώσεις, μεταφράσεις, πιστοποιήσεις ή απλά να περιμένουν στην ουρά.

Η Έρευνα Χρήσης Χρόνου (ΕΧΧ) της ΕΛΣΤΑΤ που ήδη προγραμματίζεται να διενεργηθεί το 2021 είναι μια καλή ευκαιρία να μετρηθεί χονδρικά αυτός ο χρόνος χωρίς πρόσθετο κόστος για το φορολογούμενο. Η ημερομηνία του 2021 φαντάζει πολύ μακρινή αλλά λογικά ο σχεδιασμός της έρευνας θα αρχίσει αρκετά πιο σύντομα. Χρειαζόμαστε επίσης χρόνο για να ενημερωθούν οι πολίτες και οι πολιτικοί παράγοντες ούτως ώστε να στηρίξουν την έρευνα και να αξιοποιήσουν τα ευρήματά της.

Προς τί η μέτρηση;

Ο χρόνος των πολιτών έχει αξία κι ανήκει στον ίδιους, όχι στο Κράτος. Το Κράτος έχει την εξουσία να χρησιμοποιεί ή να δεσμεύει το χρόνο μας, αλλά όχι χωρίς λόγο και όχι χωρίς προϋποθέσεις. Πρέπει είτε να λογοδοτεί (όπως αν πχ μας φορολογούσε) είτε να μας αποζημιώνει (όπως πχ αν είχε απαλλοτριώσει την περιουσία μας) είτε να μας ανταμείβει (όπως πχ αν είχε υπογράψει σύμβαση μαζί μας).

Αυτό κατά βάθος το γνωρίζουν και οι απλοί πολίτες και οι πολιτικοί. Κάθε σχεδόν κυβέρνηση (και αντιπολίτευση) υπόσχεται ένα πιο ευέλικτο και φιλικό προς το χρήστη Δημόσιο. Πώς όμως αξιολογούμε το αν ο στόχος τους έχει επιτευχθεί, και αν οι όποιες μεταρρυθμίσεις αρκούν για να αλλάξουν την καθημερινότητα των πολιτών; Για την ώρα, δεν μπορούμε να το κάνουμε παρά μόνο πολύ αποσπασματικά.

Πώς μπορεί να γίνει;

Το βασικό εργαλείο της μέτρησης μπορεί να είναι η Έρευνα Χρήσης Χρόνου, που διεξάγει η ΕΛΣΤΑΤ. Στην πρόσφατη ΕΧΧ του 2013/4 (που ήταν και η πρώτη του είδους της) συμμετείχαν 7.137 άτομα από 3.371 νοικοκυριά. Για τη μέτρηση που ζητούμε αρκούν μερικές μικρές προσαρμογές στα ερωτηματολόγια της ΕΧΧ του 2013/4, τα οποία (μαζί με τα αποτελέσματα της έρευνας) μπορεί κανείς να δει εδώ: http://www.statistics.gr/statistics/-/publication/SFA30/-

Στο ερωτηματολόγιο της ΕΧΧ, κάθε δραστηριότητα των ερωτηθέντων αντιστοιχεί σε έναν κωδικό. Οι κωδικοί προέρχονται από την Ευρωπαϊκή ταξινόµηση ACL2008 (Activity Coding List for Harmonized European Time Use Surveys) και ακολουθούν τις κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες του 2008 (HETUS 2008). Οι κωδικοί 362 (εμπορικές και διαχειριστικές υπηρεσίες) και 371 (διαχείριση υποθέσεων του νοικοκυριού) θα μπορούσαν να διασπαστούν ούτως ώστε να διακρίνονται ξεκάθαρα οι συναλλαγές με δημόσιες υπηρεσίες και η προετοιμασία τους κατ' οίκον από τις διαχειριστικές ανάγκες του νοικοκυριού.

Κάθε τοποθεσία αντιστοιχεί επίσης σε έναν κωδικό. Ο κωδικός τοποθεσίας 19 (Άλλη συγκεκριμένη τοποθεσία) θα μπορούσε να διασπαστεί ώστε να διακρίνονται ξεκάθαρα οι δραστηριότητες που λαμβάνουν χώρα σε δημόσιες υπηρεσίες.

Αν χρειαστεί η ΕΛΣΤΑΤ να καταβάλει εναρμονισμένα στοιχεία με βάση την ACL2008, είναι σχετικά απλό ζήτημα το να αθροίσει τους επιμέρους κωδικούς που προήλθαν πχ από τη διάσπαση των 362 και 371 (ας τους πούμε 362/1 και 362/2 ή 371/1 και 371/2).

Και τί θα αλλάξει;

Τα στοιχεία της ΕΧΧ μπορούν να μας πούν πόσο χρόνο αφιερώνουν οι πολίτες στο κράτος, αν αυτός αυξάνεται ή μειώνεται, και ποιές κατηγορίες πολιτών επιβαρύνονται περισσότερο – ανά ηλικία, φύλο, σύνθεση νοικοκυριού, τοποθεσία, βαθμό αστικότητας και θέση στην εργασία. Γνωρίζοντας αυτές τις λεπτομέρειες είναι πιο εύκολο να σκεφτεί κανείς λύσεις για τη δημόσια διοίκηση αλλά και να παρακολουθήσει, σε βάθος χρόνου, την αποτελεσματικότητά τους. Πιθανώς γι αυτό το λόγο και η πρώτη ΕΧΧ του 2013/4 χρηματοδοτήθηκε από το Επιχειρησιακό Πρόγραμμα «Διοικητική Μεταρρύθμιση 2007-2013.

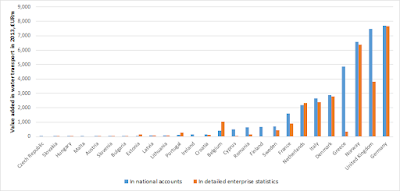

Η ΕΧΧ χρησιμοποιείται ήδη για να παράσχει συμπληρωματικές μετρήσεις στον υπολογισμό του ΑΕΠ (πχ εκτιμήσεις που σπάνια βλέπουν το φώς της δημοσιότητας σχετικά με της αξίας της απλήρωτης εργασίας των νοικοκυριών.) Η μέτρηση του χρόνου που δεσμεύει το Κράτος μπορεί κι αυτή να βελτιώσει, πχ τις εκτιμήσεις για την προστιθέμενη αξία της δημόσιας διοίκησης.

Σε βάθος χρόνου, μπορεί να πειστούν και άλλες Ευρωπαϊκές χώρες να διεξάγουν τις ίδιες μετρήσεις – με αποτέλεσμα να προκύψουν συγκρίσιμα στοιχεία.

Ανεξαρτήτως όμως από το πώς χρησιμοποιούμε τα στοιχεία, κάθε φορά που γίνεται αναφορά σε αυτά θα είναι και μια υπενθύμιση στους κυβερνώντες και στο πολιτικό προσωπικό της χώρας ότι ο χρόνος μας δεν τους ανήκει.

Δεν είμαστε παράλογοι…

Ο σκοπός αυτών των στοιχείων δεν είναι ο εντυπωσιασμός αλλά η μέτρηση. Δεν θέλουμε να νοθεύσουμε τα νούμερα με συναλλαγές ή εργασίες κατά τις οποίες ο πολίτης δεν παρέχει

ουσιαστικά την εργασία ή το χρόνο του στο Κράτος, ούτε με δραστηριότητες για τις οποίες ήδη υπάρχει λογοδοσία. Είναι σχετικά εύκολο να γίνει αυτό.

Για παράδειγμα, αν ο ερωτηθείς είναι δημόσιος υπάλληλος, εννοείται ότι η εργασία του θα συνεχίζει να εμπίπτει στους κωδικούς (δραστηριότητας και τοποθεσίας) που σχετίζονται με την κύρια εργασία. Και είναι λογικό – ο συμπολίτης αυτός πληρώνεται για την εργασία του και το Κράτος ήδη δίνει λογαριασμό και για το χρόνο εργασίας του και για την αμοιβή του.

Παρομοίως, ο χρόνος κατά τον οποίο ο πολίτης απολαμβάνει υπηρεσίες του Δημοσίου δεν έχει νόημα να μετρηθεί ως χρόνος που του ‘δεσμεύει’ το Κράτος. Για παράδειγμα, δεν

είναι προσφορά χρόνου στο Κράτος το να παρακολουθεί κανείς διαλέξεις σε ένα δημόσιο πανεπιστήμιο: αρκεί να μετρηθεί όπως και ως τώρα κάτω από τους κωδικούς 211-212 (Μαθήματα – Εργασία στο σπίτι). Η υποβολή μηχανογραφικού όμως και η συλλογή των δικαιολογητικών για την εγγραφή σε δημόσιο ΑΕΙ μπορεί να είναι διαφορετική υπόθεση.

Τέλος, όταν οι συναλλαγές με το δημόσιο συνδυάζονται με άλλες δραστηριότητες (πχ ψώνια), δεν πρέπει να χρεώνεται το δημόσιο όλες τις σχετικές δραστηριότητες και μετακινήσεις. Εφόσον υπάρχουν τα υπόλοιπα σχετικά στοιχεία, είναι σχετικά εύκολο για οποιονδήποτε ερευνητή να κάνει έναν απλό επιμερισμό.

Τι λέει η ΕΛΣΤΑΤ για όλα αυτά;

Το αίτημα απευθύνεται στην ΕΛΣΤΑΤ όχι επειδή έχει δείξει κάποια απροθυμία να ασχοληθεί με το θέμα (δεν ισχύει κάτι τέτοιο) αλλα απλώς επειδή είναι η αρμόδια αρχή. Η ΕΛΣΤΑΤ συλλέγει και αξιολογεί τακτικά προτάσεις από τους χρήστες της - δείτε πχ την πιο πρόσφατη έρευνα ικανοποίησης χρηστών:

http://www.statistics.gr/user-satisfaction-survey

Ο συντάκτης του ψηφίσματος έχει επικοινωνήσει μέσω email με ένα από τα αρμόδια άτομα και εισέπραξε μια ευγενική απάντηση, την υπόσχεση καταγραφής της πρότασής του και μερικές χρήσιμες πληροφορίες.

Όταν έρθει η ώρα να σχεδιαστεί η έρευνα του 2021, όμως, θα είναι παράλογο να αποφασίσει η ΕΛΣΤΑΤ μια σημαντική αλλαγή με βάση τα σχόλια ενός μόνο χρήστη. Ένα μαζικό αίτημα θα τη βοηθήσει να αξιολογήσει καλύτερα πόση ζήτηση υπάρχει γι αυτά τα στοιχεία και αν αξίζει τον κόπο να γίνουν οι εν λόγω αλλαγές.

Η Έρευνα Χρήσης Χρόνου (ΕΧΧ) της ΕΛΣΤΑΤ που ήδη προγραμματίζεται να διενεργηθεί το 2021 είναι μια καλή ευκαιρία να μετρηθεί χονδρικά αυτός ο χρόνος χωρίς πρόσθετο κόστος για το φορολογούμενο. Η ημερομηνία του 2021 φαντάζει πολύ μακρινή αλλά λογικά ο σχεδιασμός της έρευνας θα αρχίσει αρκετά πιο σύντομα. Χρειαζόμαστε επίσης χρόνο για να ενημερωθούν οι πολίτες και οι πολιτικοί παράγοντες ούτως ώστε να στηρίξουν την έρευνα και να αξιοποιήσουν τα ευρήματά της.

Προς τί η μέτρηση;

Ο χρόνος των πολιτών έχει αξία κι ανήκει στον ίδιους, όχι στο Κράτος. Το Κράτος έχει την εξουσία να χρησιμοποιεί ή να δεσμεύει το χρόνο μας, αλλά όχι χωρίς λόγο και όχι χωρίς προϋποθέσεις. Πρέπει είτε να λογοδοτεί (όπως αν πχ μας φορολογούσε) είτε να μας αποζημιώνει (όπως πχ αν είχε απαλλοτριώσει την περιουσία μας) είτε να μας ανταμείβει (όπως πχ αν είχε υπογράψει σύμβαση μαζί μας).

Αυτό κατά βάθος το γνωρίζουν και οι απλοί πολίτες και οι πολιτικοί. Κάθε σχεδόν κυβέρνηση (και αντιπολίτευση) υπόσχεται ένα πιο ευέλικτο και φιλικό προς το χρήστη Δημόσιο. Πώς όμως αξιολογούμε το αν ο στόχος τους έχει επιτευχθεί, και αν οι όποιες μεταρρυθμίσεις αρκούν για να αλλάξουν την καθημερινότητα των πολιτών; Για την ώρα, δεν μπορούμε να το κάνουμε παρά μόνο πολύ αποσπασματικά.

Πώς μπορεί να γίνει;

Το βασικό εργαλείο της μέτρησης μπορεί να είναι η Έρευνα Χρήσης Χρόνου, που διεξάγει η ΕΛΣΤΑΤ. Στην πρόσφατη ΕΧΧ του 2013/4 (που ήταν και η πρώτη του είδους της) συμμετείχαν 7.137 άτομα από 3.371 νοικοκυριά. Για τη μέτρηση που ζητούμε αρκούν μερικές μικρές προσαρμογές στα ερωτηματολόγια της ΕΧΧ του 2013/4, τα οποία (μαζί με τα αποτελέσματα της έρευνας) μπορεί κανείς να δει εδώ: http://www.statistics.gr/statistics/-/publication/SFA30/-

Στο ερωτηματολόγιο της ΕΧΧ, κάθε δραστηριότητα των ερωτηθέντων αντιστοιχεί σε έναν κωδικό. Οι κωδικοί προέρχονται από την Ευρωπαϊκή ταξινόµηση ACL2008 (Activity Coding List for Harmonized European Time Use Surveys) και ακολουθούν τις κατευθυντήριες οδηγίες του 2008 (HETUS 2008). Οι κωδικοί 362 (εμπορικές και διαχειριστικές υπηρεσίες) και 371 (διαχείριση υποθέσεων του νοικοκυριού) θα μπορούσαν να διασπαστούν ούτως ώστε να διακρίνονται ξεκάθαρα οι συναλλαγές με δημόσιες υπηρεσίες και η προετοιμασία τους κατ' οίκον από τις διαχειριστικές ανάγκες του νοικοκυριού.

Κάθε τοποθεσία αντιστοιχεί επίσης σε έναν κωδικό. Ο κωδικός τοποθεσίας 19 (Άλλη συγκεκριμένη τοποθεσία) θα μπορούσε να διασπαστεί ώστε να διακρίνονται ξεκάθαρα οι δραστηριότητες που λαμβάνουν χώρα σε δημόσιες υπηρεσίες.

Αν χρειαστεί η ΕΛΣΤΑΤ να καταβάλει εναρμονισμένα στοιχεία με βάση την ACL2008, είναι σχετικά απλό ζήτημα το να αθροίσει τους επιμέρους κωδικούς που προήλθαν πχ από τη διάσπαση των 362 και 371 (ας τους πούμε 362/1 και 362/2 ή 371/1 και 371/2).

Και τί θα αλλάξει;

Τα στοιχεία της ΕΧΧ μπορούν να μας πούν πόσο χρόνο αφιερώνουν οι πολίτες στο κράτος, αν αυτός αυξάνεται ή μειώνεται, και ποιές κατηγορίες πολιτών επιβαρύνονται περισσότερο – ανά ηλικία, φύλο, σύνθεση νοικοκυριού, τοποθεσία, βαθμό αστικότητας και θέση στην εργασία. Γνωρίζοντας αυτές τις λεπτομέρειες είναι πιο εύκολο να σκεφτεί κανείς λύσεις για τη δημόσια διοίκηση αλλά και να παρακολουθήσει, σε βάθος χρόνου, την αποτελεσματικότητά τους. Πιθανώς γι αυτό το λόγο και η πρώτη ΕΧΧ του 2013/4 χρηματοδοτήθηκε από το Επιχειρησιακό Πρόγραμμα «Διοικητική Μεταρρύθμιση 2007-2013.

Η ΕΧΧ χρησιμοποιείται ήδη για να παράσχει συμπληρωματικές μετρήσεις στον υπολογισμό του ΑΕΠ (πχ εκτιμήσεις που σπάνια βλέπουν το φώς της δημοσιότητας σχετικά με της αξίας της απλήρωτης εργασίας των νοικοκυριών.) Η μέτρηση του χρόνου που δεσμεύει το Κράτος μπορεί κι αυτή να βελτιώσει, πχ τις εκτιμήσεις για την προστιθέμενη αξία της δημόσιας διοίκησης.

Σε βάθος χρόνου, μπορεί να πειστούν και άλλες Ευρωπαϊκές χώρες να διεξάγουν τις ίδιες μετρήσεις – με αποτέλεσμα να προκύψουν συγκρίσιμα στοιχεία.

Ανεξαρτήτως όμως από το πώς χρησιμοποιούμε τα στοιχεία, κάθε φορά που γίνεται αναφορά σε αυτά θα είναι και μια υπενθύμιση στους κυβερνώντες και στο πολιτικό προσωπικό της χώρας ότι ο χρόνος μας δεν τους ανήκει.

Δεν είμαστε παράλογοι…

Ο σκοπός αυτών των στοιχείων δεν είναι ο εντυπωσιασμός αλλά η μέτρηση. Δεν θέλουμε να νοθεύσουμε τα νούμερα με συναλλαγές ή εργασίες κατά τις οποίες ο πολίτης δεν παρέχει

ουσιαστικά την εργασία ή το χρόνο του στο Κράτος, ούτε με δραστηριότητες για τις οποίες ήδη υπάρχει λογοδοσία. Είναι σχετικά εύκολο να γίνει αυτό.

Για παράδειγμα, αν ο ερωτηθείς είναι δημόσιος υπάλληλος, εννοείται ότι η εργασία του θα συνεχίζει να εμπίπτει στους κωδικούς (δραστηριότητας και τοποθεσίας) που σχετίζονται με την κύρια εργασία. Και είναι λογικό – ο συμπολίτης αυτός πληρώνεται για την εργασία του και το Κράτος ήδη δίνει λογαριασμό και για το χρόνο εργασίας του και για την αμοιβή του.

Παρομοίως, ο χρόνος κατά τον οποίο ο πολίτης απολαμβάνει υπηρεσίες του Δημοσίου δεν έχει νόημα να μετρηθεί ως χρόνος που του ‘δεσμεύει’ το Κράτος. Για παράδειγμα, δεν

είναι προσφορά χρόνου στο Κράτος το να παρακολουθεί κανείς διαλέξεις σε ένα δημόσιο πανεπιστήμιο: αρκεί να μετρηθεί όπως και ως τώρα κάτω από τους κωδικούς 211-212 (Μαθήματα – Εργασία στο σπίτι). Η υποβολή μηχανογραφικού όμως και η συλλογή των δικαιολογητικών για την εγγραφή σε δημόσιο ΑΕΙ μπορεί να είναι διαφορετική υπόθεση.

Τέλος, όταν οι συναλλαγές με το δημόσιο συνδυάζονται με άλλες δραστηριότητες (πχ ψώνια), δεν πρέπει να χρεώνεται το δημόσιο όλες τις σχετικές δραστηριότητες και μετακινήσεις. Εφόσον υπάρχουν τα υπόλοιπα σχετικά στοιχεία, είναι σχετικά εύκολο για οποιονδήποτε ερευνητή να κάνει έναν απλό επιμερισμό.

Τι λέει η ΕΛΣΤΑΤ για όλα αυτά;

Το αίτημα απευθύνεται στην ΕΛΣΤΑΤ όχι επειδή έχει δείξει κάποια απροθυμία να ασχοληθεί με το θέμα (δεν ισχύει κάτι τέτοιο) αλλα απλώς επειδή είναι η αρμόδια αρχή. Η ΕΛΣΤΑΤ συλλέγει και αξιολογεί τακτικά προτάσεις από τους χρήστες της - δείτε πχ την πιο πρόσφατη έρευνα ικανοποίησης χρηστών:

http://www.statistics.gr/user-satisfaction-survey

Ο συντάκτης του ψηφίσματος έχει επικοινωνήσει μέσω email με ένα από τα αρμόδια άτομα και εισέπραξε μια ευγενική απάντηση, την υπόσχεση καταγραφής της πρότασής του και μερικές χρήσιμες πληροφορίες.

Όταν έρθει η ώρα να σχεδιαστεί η έρευνα του 2021, όμως, θα είναι παράλογο να αποφασίσει η ΕΛΣΤΑΤ μια σημαντική αλλαγή με βάση τα σχόλια ενός μόνο χρήστη. Ένα μαζικό αίτημα θα τη βοηθήσει να αξιολογήσει καλύτερα πόση ζήτηση υπάρχει γι αυτά τα στοιχεία και αν αξίζει τον κόπο να γίνουν οι εν λόγω αλλαγές.